the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Assessing the vulnerability of family farms to rainfall-induced flood risks in the municipality of Kandi, Benin

Sénadé Sylvie Hounzinme

Monsoundé Etienne Dossou

Tarick Adamou

Madjidou Oumorou

The study assesses the vulnerability of family farms to rainfall-induced flooding in the municipality of Kandi, northern Benin, using the IPCC vulnerability framework based on exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Data were collected from 80 agricultural producers across ten villages through structured interviews and analyzed across five types of capital: human, physical, financial, social, and natural. Results reveal significant disparities between farm categories. Small farms (≤ 5 ha) exhibit very high vulnerability (4.5/5), marked by low education levels (38.9 % uneducated), limited mechanization (83.3 % without access), and poor credit availability (77.8 % excluded). Medium farms (5–20 ha) show moderate vulnerability (≈ 3.0/5), with 61% having access to mechanization and 46.3% to credit, but still constrained by low income diversification. Large farms (>20 ha) demonstrate low vulnerability (≈ 1.5/5), benefiting from strong assets: 76.2 % mechanized, 71.4 % with credit access, 90.5 % participating in cooperatives, and 57.1 % cultivating fertile soils. The analysis highlights an inverse correlation between farm size and flood vulnerability, reflecting structural inequalities in access to productive and adaptive resources. Strengthening human and financial capital among smallholders – through literacy, agricultural training, microfinance, and cooperative mechanization – is crucial to enhance resilience. This research contributes to climate vulnerability literature by integrating socio-economic and biophysical indicators into a composite framework, emphasizing the multidimensional nature of vulnerability and the need for inclusive adaptation policies in northern Benin.

- Article

(797 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

Family farming plays a central role in ensuring food security and sustaining rural livelihoods, particularly in developing countries (Chimi et al., 2023; Bachewe et al., 2018). However, these farms are increasingly exposed to climate-related risks such as floods induced by intense rainfall events, which can cause crop losses, soil degradation, and long-term declines in agricultural productivity (IPCC, 2014; FAO, 2022).

In Benin, particularly in the municipality of Kandi, floods have significant adverse effects on agricultural production (Adjakpa, 2016). This predominantly rural area depends heavily on agriculture, especially the cultivation of maize, cotton, millet, cowpea, and groundnut, which remain vulnerable to climatic extremes (Biaou, 2023). Heavy rainfall events and resulting floods affect crop yields directly, thereby increasing the exposure and sensitivity of family farms (Dimon, 2008).

Although numerous scientific studies have examined the biophysical impacts of flooding, fewer have conducted a comprehensive assessment of family farm vulnerability that integrates exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity. Such an approach is essential for understanding how climatic hazards affect farming systems (Tanner et al., 2015; Stringer et al., 2020). This gap in the literature justifies the present study, which aims to quantify and analyze the vulnerability of family farms to flooding by identifying the socio-economic, institutional, and environmental factors shaping this vulnerability.

In this study, vulnerability is defined as the propensity of farming systems to experience damage or loss in the face of flooding, determined by their exposure to flood events, the sensitivity of crops and infrastructure, and the adaptive capacity of households (IPCC, 2014; GIEC, 2014). Assessing this vulnerability helps identify the farms most at risk and determine which dimensions – physical, social, or economic – require priority intervention (Füssel, 2007; Cutter et al., 2008).

Thus, the relevance of this research lies in implementing an integrated assessment of the vulnerability of family farms to flooding by combining biophysical and socio-economic indicators, while highlighting effective adaptation strategies (Di Falco et al., 2011; Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr, 2016; Mortimore and Adams, 2020).

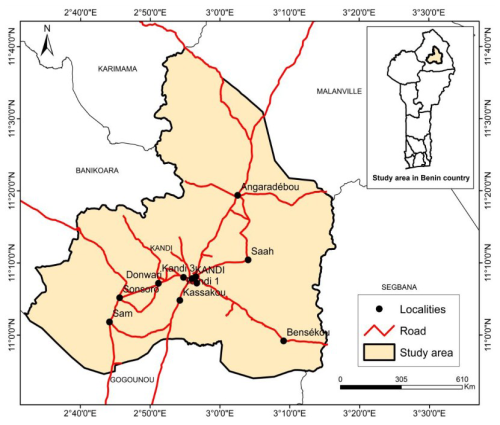

2.1 Study area

The commune of Kandi is located in northern Benin, specifically at latitude 11°07′43′′ N and longitude 2°56′13′′ E (Fig. 1). It experiences a Sudanian climate characterized by two distinct seasons: a rainy season (May to October) with irregular but often intense precipitation (800 to 1300 mm yr−1), and a dry season (November to April) marked by high temperatures (17 to 39 °C), with heat peaks in March–April and the Harmattan, a dry and dusty wind, blowing between December and February.

Climate variability, exacerbated by climate change, intensifies these extreme phenomena, alternating between pluvial floods that wash away seedlings and recurrent droughts that limit water availability for irrigation and livestock. The low permeability of tropical ferruginous soils promotes runoff, thereby increasing flood risks. Finally, the limited availability of temporary watercourses (tributaries of the Alibori) during the dry season exacerbates water stress for agriculture and local populations.

2.2 Methodology

This study adopted the vulnerability assessment approach developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC, 2014). According to this approach, three essential elements influence vulnerability to extreme weather events: exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity.

In Kandi municipality, exposure corresponds to the frequency and intensity of rainfall-induced floods and their location on farms. Sensitivity encompasses intrinsic farm characteristics, such as cultivated area, crop type, dependency on climatic conditions, and the importance of subsistence agriculture for household livelihoods. Adaptive capacity reflects the resources available to reduce flood impacts, including access to information, drainage infrastructure, early warning systems, and local agricultural strategies.

2.2.1 Data Collection

Field visits were conducted to collect data through individual surveys of agricultural producers identified with the assistance of an officer from the Territorial Agricultural Development Agency (ATDA). The target population was sampled in ten villages based on flood frequency and agricultural activity diversity. In each village, eight household heads were selected according to cultivated area, totaling 80 respondents.

Structured questionnaires were administered during individual interviews with household heads or adult members. They collected detailed information on:

-

Demographic data: age, sex, household size, education level, marital status, etc.

-

Socio-economic data: income sources, living standards, access to basic services (water, electricity, health, education).

-

Environmental data: waste management, access to natural resources, impact of human activities on the environment.

-

The survey was conducted from March to April 2024 by a team of two trained enumerators. A pre-test phase was carried out on a subsample to evaluate the clarity and relevance of the questions and make necessary adjustments.

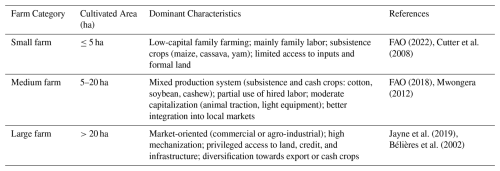

Table 1 categorizes farms according to cultivated area.

Data collection was based on individual interviews conducted with 80 agricultural producers operating farms. Participants were selected using a purposive sampling approach to ensure the representativeness of the sample. Data were collected through a digitized questionnaire using Kobo Toolbox, enabling rapid and structured data entry. The collected data pertain to producers' perceptions, the impacts of rainfall-induced flooding on farms, and the adaptation measures implemented.

2.2.2 Data analysis

Vulnerability of family farms in Kandi was assessed by integrating exposure, sensitivity, and adaptive capacity, influenced by five types of capital:

-

Human capital: knowledge, skills, experience, education, and training of farmers.

-

Physical capital: available infrastructure, agricultural equipment, drainage, and storage systems.

-

Financial capital: access to credit, subsidies, and farm-generated income.

-

Social capital: community networks and local solidarity facilitating access to resources and information.

-

Natural capital: natural resources available, such as soil quality, water access, and biodiversity.

The analysis combined assessment of flood exposure, farm sensitivity, and adaptive capacity based on the five types of capital. Each indicator was normalized between 0 and 1. A composite vulnerability index (IV) was calculated as:

where E = exposure, S = sensitivity, C = adaptive capacity.

The vulnerability index ranges from 0 to 1 and classifies farms into three levels: low (0–0.33), medium (0.34–0.66), and high (0.67–1.0) following Füssel (2007).

3.1 Farm Capital Analysis

The analysis highlights significant disparities among farms according to their size. Regarding human capital, small-scale farms are characterized by a low level of education: 38.9 % of farm heads have no formal education, and 44.4 % have only completed primary school, compared to 12.2 % and 48.8 %, respectively, for medium-sized farms. Large farms stand out with a high proportion of producers having attained secondary (47.6 %) or tertiary education (28.6 %). In terms of agricultural experience, the majority of large farms (81 %) have accumulated more than 10 years of experience, compared to 44.5 % for small farms, reflecting better technical expertise and adaptive capacity to hydrological shocks (Table 2).

Physical capital confirms these gaps: 33.3 % of small farms lack any agricultural equipment, and 55.6 % rely solely on manual tools. In contrast, 42.9 % of large farms own a tractor or a complete set of equipment. Access to mechanization remains marginal among small farms (16.7 %) compared to 76.2 % among large ones. Regarding storage facilities, 38.9 % of small farms have none, whereas 76.2 % of large farms possess advanced infrastructures (granaries, silos). These contrasts indicate a heightened structural vulnerability of small farms, which are more exposed to post-harvest losses during flood periods.

Concerning financial capital, 77.8 % of small farms have no access to credit, compared to 53.7 % of medium and only 28.6 % of large farms. Income follows the same trend: 72.2 % of small farms generate less than 2 million FCFA per year, while 71.4 % of large farms exceed 5 million FCFA. Furthermore, income diversification is very limited among small farms (55.6 % rely on a single source), whereas 57.1 % of large farms have more than two sources, strengthening their economic resilience to rainfall variability.

Regarding social capital, participation in associations or cooperatives is limited among small farms (44.4 %), but reaches 90.5 % among large ones, facilitating access to information, inputs, and mutual aid networks. The strength of mutual support networks is considered weak in 50 % of small farms, moderate in 48.8 % of medium ones, and strong in 57.1 % of large farms. Similarly, market access through social networks is weak for 44.4 % of small farms but strong for 66.7 % of large farms, which represents a significant advantage for post-flood recovery.

Finally, natural capital shows that soil quality is considered poor in 33.3 % of small farms, compared to only 4.8 % of large ones, while 57.1 % of the latter enjoy fertile soils. In terms of cultivated area, small farms are limited to less than 5 ha, medium ones range between 5 and 20 ha, and large farms exceed 20 ha, confirming the concentration of productive resources among larger holdings.

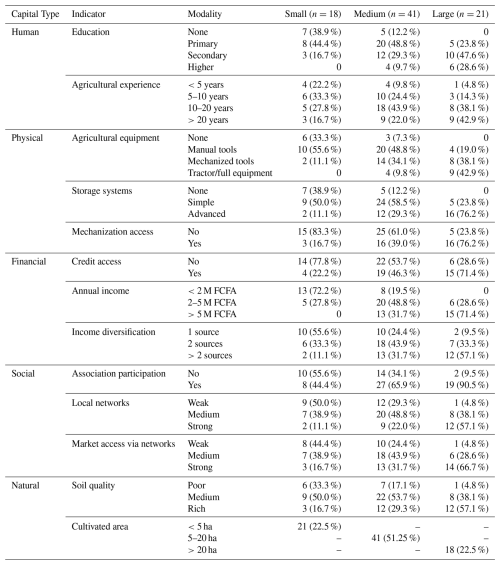

3.2 Vulnerability Analysis

The analysis of Fig. 2 revealed a clear differentiation in vulnerability according to farm size. Small farms exhibited a very high average vulnerability score of 4.5/5, reflecting strong exposure and low resilience. This high level is explained by low human capital (≈ 39 % without education), nearly absent mechanization (83.3 % without access), and very limited credit access (77.8 % without financing). Storage structures and diversified income sources were rare, further increasing vulnerability during floods.

Medium farms had an intermediate vulnerability score of approximately 3.0/5, with slightly stronger capital: 61 % had mechanization access, 46.3 % had credit, and 43.9 % had diversified income sources. However, structural weaknesses (low education, limited financial resources) maintained significant exposure to risk.

Large farms fell into the low vulnerability category (≈ 1.5/5), benefiting from strong capital: 76.2 % had mechanization access, 71.4 % had credit support, 90.5 % participated in associations, 57.1 % had more than two income sources, 57.1 % cultivated rich soils, and 76.2 % used advanced storage infrastructure.

These results indicate an inverse correlation between farm size and flood vulnerability: smaller farms are highly vulnerable, medium farms moderately so, and large farms are resilient. This hierarchy reflects stark inequalities in access to productive and adaptive resources, a key challenge for local climate risk management in Kandi.

3.3 Discussion

The study demonstrates a clear inverse relationship between farm size and vulnerability to rainfall-induced floods in Kandi. The observed vulnerability hierarchy very high for small farms (4.5/5), moderate for medium farms (3.0/5), and low for large farms (1.5/5) – reflects deep structural inequalities in rural agricultural systems in West Africa (FAO, 2018; Füssel, 2007). These disparities arise from differences in access to productive capital, adaptive capacity, and integration into socio-economic networks (Tanner et al., 2015; Stringer et al., 2020).

The low education level among 83.3 % of small farm heads (none or primary) limits their ability to interpret climate information, adopt agricultural innovations, and plan preventive measures. This aligns with findings from Alobo Loison (2017) in Burkina Faso and Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr (2016) in Ghana, demonstrating that human capital directly affects risk understanding and the adoption of climate-smart strategies. Conversely, large farm operators, with 76.2 % having at least secondary education, possess cognitive and organizational advantages, enabling the integration of innovative practices such as drainage, crop diversification, and strategic rotation (Amouzou et al., 2022).

Physical capital is pivotal for flood resilience. In Kandi, only 16.7 % of small farms had mechanization access versus 76.2 % of large farms. Lack of equipment prevents rapid soil preparation and replanting after extreme rainfall, prolonging post-flood vulnerability (Boko et al., 2023). Furthermore, the absence of advanced storage infrastructure (38.9 % of small farms) increases post-harvest losses and limits seed preservation. Studies in Niger and Mali confirm that mechanization and storage are strongly correlated with agricultural income stability under rainfall variability (Di Falco et al., 2011; Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr, 2016).

Credit access represents a major barrier for small farmers: 77.8 % lack formal financing, whereas 71.4 % of large farms benefit from financial support. Limited liquidity prevents preventive investments (dikes, drainage channels, water pumps), increasing sensitivity to hydrological shocks (FAO, 2022; Tambo and Wünscher, 2017). At Kandi, this financial inequality explains why 72.2 % of small farms earn less than 2 million FCFA/year, while 71.4 % of large farms exceed 5 million FCFA. Limited income diversification further accentuates dependency on rainfall and reduces economic flexibility (Hansen et al., 2021).

Social capital emerges as a critical mitigating factor. Large farms (90.5 %) actively participate in cooperatives or associations, compared with 44.4 % of small farms. These structures facilitate access to information, post-crisis aid, and markets, reducing institutional vulnerability (Cinner et al., 2018; Chandra et al., 2019). Strong local networks were observed in 57.1 % of large farms versus 50 % of small farms lacking such networks. Several studies show that social networks and community dynamics enhance collective disaster response in rural Sub-Saharan Africa (Thornton et al., 2022).

Regarding natural capital, differences are significant: 57.1 % of large farms cultivate rich soils versus 16.7 % of small farms. Average cultivated area for small farms does not exceed 5 ha, limiting spatial adaptation practices (fallowing, crop rotation, topographical diversification). These observations align with Mortimore and Adams, who emphasize that soil quality and area directly influence ecological buffering capacity against floods (Mortimore and Adams, 2020). Small farms on low, clayey lands suffer greater water saturation, soil structure degradation, and yield reduction.

The Kandi data support the systemic vulnerability approach proposed by Cutter et al. (2008) and Füssel (2007), where social, economic, and environmental dimensions interact to form a multidimensional risk structure. Vulnerability is not solely linked to physical exposure but results from structural constraints and resilience deficits.

Policy recommendations include targeted strengthening of deficient capitals: literacy and agrometeorological training programs to enhance small farmers' analytical and planning skills (FAO, 2022); shared mechanization via cooperatives to offset investment inequalities (Jayne et al., 2019); expanded climate-focused microfinance to support resilient infrastructure (Nyantakyi-Frimpong and Bezner Kerr, 2016); and community-based mutual flood insurance funds inspired by successful initiatives in Senegal and Rwanda (Fadeyi, 2018).

This study demonstrates that farm vulnerability in Kandi is not homogeneous but structured by inequalities in access to productive capital. Small farms, characterized by low income, low education, and social isolation, remain most exposed to flooding, whereas large farms possess resources to absorb and recover from hydrological shocks. These findings advocate for adaptive justice policies that foster inclusive resilience for the most vulnerable agricultural producers in northern Benin.

Scientifically, the study contributes to the literature on African agricultural climate vulnerability by integrating five types of capital (human, physical, financial, social, natural) into a coherent analytical framework. It highlights the relevance of an integrated approach combining socio-economic and biophysical data.

The R software used in this study is freely available (https://www.r-project.org/, R Development Team, 2024). Microsoft Excel was also used for data processing and analysis. The code is not publicly accessible. Please contact the authors if you are interested in accessing this research code.

The socio-economic data collected in this study are not publicly available. Please contact the authors if you are interested in accessing the socio-economic data used in this research.

SSH and MO defined the framework of the paper. MED applied statistical, mathematical, computational, and other formal techniques to analyze and synthesize the study data. TA collected the data. SSH prepared the manuscript with contributions from all co-authors.

The contact author has declared that none of the authors has any competing interests.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Circular Economy and Technological Innovations for Resilient Water and Sanitation Systems in Africa”. It is a result of the 1st Edition of the C2EA Water and Sanitation Week on the Circular Economy and Technological Innovations, Cotonou, Benin, 3–6 December 2024.

Many contributors participated in the data collection for the preparation of this publication. We thank the communities of the Commune of Kandi as well as the ADTA for facilitating data collection in the field.

This paper was edited by Aymar Bossa and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

Adjakpa, T. T.: Gestion des risques hydro-pluviométriques dans la vallée du Niger au Bénin: Cas des inondations des années 2010, 2012 et 2013 dans les communes de Malanville et de Karimama, Université d'Abomey-Calavi mémoire, https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12177/13086 (last access: 11 February 2026), 2016.

Alobo Loison, S. H.: Survival options, processes of change and structural transformation: Livelihood diversification among smallholder households in rural Sub-Saharan Africa, Doctoral dissertation, Lund University, Faculty of Social Sciences, 230 pp., Lund University, https://www.supagro.fr/theses/extranet/17-0022_Alobo_Loison.pdf (last access: 11 February 2026), 2017.

Amouzou, K. A., Tovihoudji, P. G., and Biaou, W.: Farm mechanization and climate resilience in Benin, J. Rural Stud., 93, 311–322, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.06.015, 2022.

Bachewe, F. N., Berhane, G., Minten, B., and Taffesse, A. S.: Agricultural transformation in Africa? Assessing the evidence in Ethiopia, World Dev., 105, 286–298, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.05.041, 2018.

Bélières, J.-F., Bosc, P.-M., Faure, G., Fournier, S., and Losch, B.: Quel avenir pour les agricultures familiales d'Afrique de l'Ouest dans un contexte libéralisé?, 48 pp., CIRAD – Agritrop., https://agritrop.cirad.fr/512676/1/ID512676.pdf (last access: 13 January 2026), 2002.

Biaou, W. E. N.: Analyse de l'écosystème et des interactions entre les acteurs de l'agroéquipement à Kandi au Nord du Bénin, Université de Parakou thèse, https://agritrop.cirad.fr/609188/1/Mémoire_Master 2_ESR_BIAOU W. Espérance Nazaire Corrigé.pdf (last access: 11 February 2026), 2023.

Boko, M., Zannou, A., and Agossou, D. J.: Climate risks and rural livelihoods in northern Benin, Environ. Sci. Policy, 145, 62–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2023.03.002, 2023.

Chandra, A., McNamara, K. E., and Dargusch, P.: Climate-smart community resilience: Understanding the complexities of social resilience building in developing countries, Clim. Dev., 11, 212–224, https://doi.org/10.1080/17565529.2018.1442797, 2019.

Chimi, P. M., Mala, W. A., Abdel, K. N., Fobane, J. L., Essouma, F. M., Matick, J. H., and Bell, J. M.: Vulnerability of family farming systems to climate change: The case of the forest–savannah transition zone, Centre Region of Cameroon, Res. Glob., 7, 100138, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resglo.2023.100138, 2023.

Cinner, J. E., Adger, W. N., Allison, E. H., Barnes, M. L., Brown, K., Cohen, P. J., and Wamukota, A.: Building adaptive capacity to climate change in tropical coastal communities, Nat. Clim. Change, 8, 117–123, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41558-017-0065-x, 2018.

Cutter, S. L., Barnes, L., Berry, M., Burton, C., Evans, E., Tate, E., and Webb, J.: A place-based model for understanding community resilience to natural disasters, Glob. Environ. Change, 18, 598–606, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2008.07.013, 2008.

Di Falco, S., Veronesi, M., and Yesuf, M.: Does adaptation to climate change provide food security? A micro-perspective from Ethiopia, American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 93, 825–842, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajae/aar006, 2011.

Dimon, R.: Adaptation aux changements climatiques : Perceptions, savoirs locaux et stratégies d'adaptation développées par les producteurs des communes de Kandi et de Banikoara, au Nord du Bénin, Université d'Abomey-Calavi thèse, https://agritrop.cirad.fr/573169/ (last access: 11 February 2026), 2008.

Fadeyi, O. A.: Smallholder agricultural finance in Nigeria: The research gap, Journal of Development and Agricultural Economics, 10, 367–376, https://doi.org/10.5897/JDAE2018.0976, 2018.

FAO: Agricultural productivity and family farming systems in Sub-Saharan Africa, FAO report, https://openknowledge.fao.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/c9dcda53-ff1a-4405-b1d1-1ecb61fca741/content (last access: 11 February 2026), 2018.

FAO: Analyse de l'impact du changement climatique sur la production agricole au Bénin, FAO report, https://agris.fao.org/search/en/providers/122444/records/6878fbc95d9ad5f58d6099e4?utm_source=chatgpt.com (last access: 11 February 2026), 2022.

Füssel, H.-M.: Vulnerability: A generally applicable conceptual framework for climate change research, Glob. Environ. Change, 17, 155–167, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2006.05.002, 2007.

GIEC: Changements climatiques 2014: Impacts, adaptation et vulnérabilité, WGII AR5 report, https://www.ipcc.ch/report/ar5/wg2 (last access: October 2024), 2014.

Hansen, J., Hellin, J., Rosenstock, T., Fisher, E., Cairns, J., Stirling, C., and Twomlow, S.: Climate risk management and insurance in Africa's agriculture, Glob. Environ. Change, 70, 102318, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102318, 2021.

IPCC: Résumé à l'intention des décideurs – Changements climatiques 2014: Impacts, adaptation et vulnérabilité. Contribution du groupe de travail II au cinquième rapport d'évaluation du GIEC. Organisation météorologique mondiale et Programme des Nations Unies pour l'environnement, https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/03/ar5_wgII_spm_fr-2.pdf (last access: 11 February 2026), 2014.

Jayne, T. S., Chamberlin, J., and Headey, D.: Land pressures, the evolution of farming systems, and development strategies in Africa, Food Policy, 84, 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.03.009, 2019.

Mortimore, M. and Adams, W. M.: Resilient livelihoods and adaptive land management in West Africa, Glob. Environ. Change, 64, 102118, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2020.102118, 2020.

Mwongera, C.: How smallholder farmers cope with climate variability: Case study of the Eastern slope of Mount Kenya (Thèse de doctorat, Montpellier SupAgro), 153 pp., AGRITROP – CIRAD, https://agritrop.cirad.fr/571093/1/document_571093.pdf (last access: 13 February 2026), 2012.

Nyantakyi-Frimpong, H. and Bezner Kerr, R.: The relative importance of climate change in the smallholder farming context, Climatic Change, 135, 143–156, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2015.03.003, 2016.

R Development Team: The R Project for Statistical Computing, https://www.r-project.org/ (last access: October 2024), 2024.

Stringer, L. C., Fraser, E. D. G., and Harris, D.: Adaptation and development pathways for different types of farmers, Environ. Sci. Policy, 104, 174–189, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envsci.2019.11.013, 2020.

Tambo, J. A. and Wünscher, T.: Enhancing resilience to climate shocks through farmer innovation, Environ. Res. Lett., 12, 125005, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-017-1113-9, 2017.

Tanner, T., Lewis, D., Wrathall, D., Bronen, R., Cradock-Henry, N., Huq, S., and Wilkinson, E.: Livelihood resilience in the face of climate change, Nat. Clim. Change, 5, 23–26, https://doi.org/10.1038/nclimate2431, 2015.

Thornton, P. K., Whitbread, A., Baedeker, T., Cairns, J., and Vermeulen, S.: Complex vulnerabilities and resilience pathways in African agriculture, Agric. Syst., 195, 103278, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agsy.2021.103278, 2022.