the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License.

Sustainable water management for rice cultivation under climate change: a case study of the Lower Ouémé Valley, Southern Benin

Marilyn Karen Soudé

Luc Ollivier Sintondji

David Houéwanou Ahoton

René Bodjrènou

In Benin, the Lower Ouémé Valley is a region of intense agricultural activity whose soil, hydrological, and climatic conditions are favourable to rice cultivation. Despite this potential, water management remains one of the challenges facing rice production in the area. The development of new land management approaches and agricultural practices is an ideal alternative for improving water management for agricultural production in a context of climate variability. Among these, the Smart-Valleys (SV) land management approach and the System of Rice Intensification (SRI) have been introduced to make rice production profitable in several regions of West Africa. This study aims to compare two land management approaches (Smart-valleys vs. Conventional) and three levels of irrigation, namely Low Variable Irrigation (IR1), Low Constant Irrigation (IR2), and Intermittent Irrigation (IR3) for efficient water management in rice production in the lower Ouémé valley. The experimental design consists of split plots with two replicates per treatment, where the management approach and irrigation levels represent the primary and secondary factors, respectively. The results of the experiment show that Smart-valleys (SV) management has a positive effect on yield (p-value = 0.01) and water productivity (p-value < 0.001). As for irrigation, the IR3 method yields the best performance in terms of water productivity (p-value < 0.001). In addition, the SV-IR2 combination maximizes paddy rice yields (8.5 t ha−1, an increase of 4.7 t ha−1), while the SV-IR3 combination optimizes water productivity (1.4 kg m−3, an increase of 1.06 kg m−3). This highlights the importance of an integrated approach that combines appropriate land management and optimal irrigation strategies to maximize water efficiency in rice production systems. An economic analysis of the different treatments will help identify the best approach to combine yields, water use, and profitability.

- Article

(443 KB) - Full-text XML

- BibTeX

- EndNote

The Lower Ouémé Valley (LOV), located in southern Benin, is recognized as one of the country's most favorable agricultural production regions due to its floodplains rich in hydromorphic soils and the presence of a major water source, the Ouémé River (Hounkanrin, 2015). These various assets make it an ideal location for rice cultivation, especially in a context marked by increasingly irregular rainfall as a result of climate change (Seidou et al., 2021). According to Arouna et al. (2017), wetlands, particularly lowlands and floodplains, have significant potential for improving rice production by mitigating the uncertainties associated with rainfall variability. Annual river flooding in the lower Ouémé valley deposits silty alluvium, which naturally renews soil fertility and creates favorable conditions for rice cultivation (Agossou et al., 2017). According to Gbenou (2013), rice production in the LOV has a long history dating back to the 1960s, when the first schemes were established by the Société Nationale d'Aménagement et de Développement de la Vallée de l'Ouémé (SADEVO) and the Société Nationale d'Irrigation et d'Aménagement Hydro-agricole (SONIAH). More recently, in Benin, decentralization has encouraged local governments to promote the rice sector through the development and implementation of municipal development plans. In comparison to other agricultural activities, rice production rates in the municipalities of Adjohoun, Aguégués, Bonou, and Dangbo were 39 %, 35 %, 12 %, and 35 %, respectively (Ahouandogbo, 2022). Despite the potential of arable land and investments made, rice production in the lower Ouémé valley continues to face water management challenges, such as poor water control on plots, difficult access to water for sloped plots, and excessive flooding of low-slope plots (Gbenou, 2013; Hounkanrin, 2015; Masiyandima et al., 2013). These water management challenges, combined with the negative effects of climate change, such as dry spells and decreasing rainfall, limit the availability of water for crop development, resulting in relatively low rice yields (Kouhoundji, 2010). In this context, effective water management and the improvement of existing agricultural practices present a promising opportunity to increase rice productivity. Bouman et al. (2005) and Thakur et al. (2011) found that reduced tillage, good soil leveling, intermittent irrigation and drainage, raised bed cultivation, mulching, and aerobic rice cultivation can all save water in rice fields. Furthermore, the use of participatory land management approaches such as Smart-valleys provides an alternative to traditional management methods that are ineffective for integrated water resource management in lowlands where poor water management is a major impediment to rice production (Dossou-Yovo et al., 2022). Fashola et al. (2002) define the Smart-valleys approach as a plot of land that has been developed, plowed, leveled, and delimited by dikes and levees to promote better water management for rice cultivation. This land management approach enables the maintenance of uniform moisture levels within the plots based on crop requirements. Arouna et al. (2017) found that adopting Smart-valleys technology in Benin's lowlands increased rice yields by 0.9 t ha−1. However, few studies have looked at how Smart-valley management and irrigation management practices affect rice system performance in the LOV. It is essential to understand the extent to which these practices can help to increase rice productivity in the face of climate change.

2.1 Study area

This study was carried out in the lower Ouémé Valley (LOV), specifically in the municipality of Bonou. This municipality is situated between 6°72′ and 6°95′ north latitude and 2°15′ to 2°40′ east longitude. It is bounded by the municipality of Ouinhi to the north, Adjohoun to the south, Sakété and Adja-Ouèrè to the east, and Zê and Zogbodomè to the west. It covers 250 km2. It has a lot of fertile land that's ideal for rice production. As a result, the Gbadohouito lowlands were selected as the case study site for this experiment. Figure 1 illustrates the geographical location of the municipality of Bonou and the case study site in the lower Ouémé valley.

2.2 Description of factors

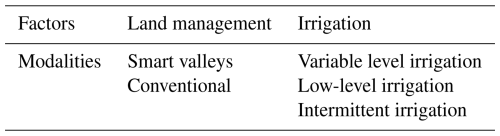

To conduct this research, two factors influencing rice production in the LOV were considered: land management and irrigation. Land management is seen as an essential practice for optimizing water and nutrient management in rice production systems. Two management approaches were evaluated in this study to improve water management for rice production. The first level, “Smart-valleys”, is a type of land management that enables farmers to improve water control at a low cost by designing and building drainage axes for the installation of irrigation canals, as well as creating fields surrounded by dikes and leveled according to topological conditions (Dossou-Yovo et al., 2022). In this type of land management, the plots are small, and plowing is done perpendicular to the slope to keep the water level uniform throughout the plots. In “conventional” management, plots are large and not plowed or leveled. Farmers believe that reduced plowing and no leveling make it easier to work the valley's clay soils and have no effect on rice production. Water management is an essential component of increasing rice productivity and sustainability. In this context, three water management methods were tested on rice fields to improve irrigation efficiency. These include variable-level irrigation (IR1), a technique in which more water (5 cm) is applied at the start of the cycle, particularly between transplanting and maximum tillering, before being reduced to 2 cm until the last two weeks before harvest. This strategy makes it possible to meet the high water requirements of rice during the tillering phase and then limit water supply once the plants are well established (Bouman et al., 2005). The second level, low-level irrigation (IR2), keeps a water depth of 2 cm throughout the production cycle, with the exception of the last two weeks before harvest, when water is gradually withdrawn to help grain ripen. This method is often associated with the System of Rice Intensification (SRI), which aims to reduce water consumption while increasing productivity. The final method, known as intermittent irrigation (IR3), is an alternate wetting and drying (AWD) method distinguished by its ability to significantly reduce the amount of irrigation water used in rice fields while maintaining yields, thereby increasing water productivity. This practice involves applying a thin layer of 2 cm of water, allowing it to evaporate until slight cracks appear in the soil, and then applying another layer of water. This technique contradicts traditional irrigation practices, in which rice fields are kept flooded throughout the growing season. Table 1 contains information about the various factors used.

2.3 Experimental design

At the Gbadohouito site, the soils are temporarily hydromorphic and have a high organic matter content due to alluvial deposits. They are also deep, which encourages proper crop rooting. The trials were carried out over a period of four months, from mid-May to mid-September 2024. This period represents the transition phase between the long rainy season (March–June) and the short dry season (July–August), providing an opportunity to characterize and incorporate the seasonal variability specific to the study area into the agronomic performance analysis. The experimental design is a split-plot layout with two replicates per treatment, with land management and irrigation as the primary and secondary factors, respectively. The site is divided into two blocks: 3750 m2 for Conventional development (AC) and 600 m2 for Smart-valleys development (SV). Six 25 m × 25 m plots were established within a conventionally developed block. In the second block, the smart-valleys approach was used to create six 10 m × 10 m plots. Irrigation treatments (IR1, IR2, and IR3) were applied at random to the experimental plots in two replicates. Plant management and fertilization in the various test plots were carried out using the principles of the System of Rice Intensification (SRI). In practice, this entails growing rice with very little seed, water, or fertilizer on organically rich soil. After preparing the test plots for the various treatments, the nursery was established with certified IR 841 rice seeds at a rate of 10 kg ha−1. Seedlings (15–18 d old) were transplanted at 25 cm × 25 cm intervals, resulting in a density of 16 plants m−2. Organic and chemical fertilizers were used as amendments to increase production in accordance with SRI recommendations. The organic fertilizer used was manure, with 5 t ha−1 spread as basal fertilizer. For maintenance fertilization, 100 kg ha−1 of NPK was applied at transplanting, and 100 kg ha−1 of urea was spread in two fractions, 7 to 10 d after transplanting and again at panicle initiation (between the 30th and 40th day after the first fraction). Manual weeding was used to maintain the plots. Weed growth was severely hampered by the presence of a layer of water in most experimental units.

2.4 Water use and yield measurement

The rain gauge was installed on-site to monitor precipitation during the trial period and determine the amount of rainwater consumed by the plants. In addition, the limnimeter was used to monitor the water level per treatment, allowing for supplementary irrigation with a motor pump. The volumes of water used at regular intervals in each plot were calculated using the flow rate and irrigation time. To assess yield, each experimental unit was divided into 1 m2 squares (3 for 10 m × 10 m plots and 5 for 25 m × 25 m plots). The squares accounted for all of the factors' modalities. Rice and straw samples were harvested and dried at 105 °C for 72 h before being extrapolated to the hectare to calculate rice grain yield.

2.5 Data analysis

Grain yield (Y) and water productivity (WP) were used as response variables in the study. Y was defined as the quantity of paddy rice grains harvested per hectare. Water productivity is the ratio of agricultural production (paddy rice) to water used, measured in kg m−3. It was calculated using Eq. (1) (Kambou et al., 2014):

Y is grain yield, (P) and (I) are the cumulative precipitation and irrigation during the growing period, respectively.

To identify significant treatment differences, the collected data subjected to analysis of variance (ANOVA) and multiple linear regression analysis using R software (version 4.3.2). ANOVA is a popular statistical method for determining the effect of multiple factors on a response variable by comparing the means of different groups. It is especially important for agronomic research, such as that conducted on rice farming practices in the LOV. This method identifies and quantifies the significant factors influencing key variables such as yield and water productivity. Multiple regression is used to quantify the relationship between land use, water management, and variations in yield and water productivity. Statistical tests, such as the coefficient significance test, can be used to determine whether each practice has a significant impact on response variables (Montgomery et al., 2021). The mean separation was carried out with the least significant difference (LSD) at a 5 % significance level.

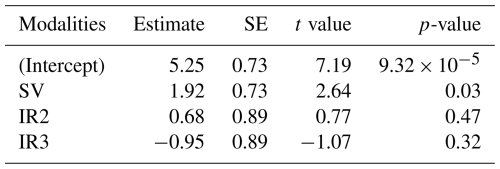

3.1 Effect of factors on rice yield

Table 2 shows the average yields obtained using land management methods and irrigation systems. The results show that developments using the Smart-valleys approach produce yields ranging from 6 to 8.5 t ha−1, with an average of 7.1 t ha−1, regardless of the type of irrigation used. In comparison, conventional developments produce yields ranging from 3.8 to 6.4 t ha−1, with an average of 5.1 t ha−1. These findings highlight a clear advantage in production performance in plots developed using the Smart-valleys approach, with an average gain of 2 t ha−1, representing a 39 % increase in rice yield over conventional developments. The mean comparison analysis confirms these findings, demonstrating that the type of land development has a significant impact on rice yield (p-value = 0.01). This significance suggests that the Smart-valleys approach, which is based on integrated optimization of water management and farming practices, significantly improves rice agronomic performance. Thus, the findings support the hypothesis that improved water management and participatory hydraulic development planning are critical levers for increasing rice productivity in the studied areas in a long-term manner. In terms of irrigation levels, plots with IR2 irrigation offer a higher yield than those with IR3 irrigation, while the average yield obtained on IR1 plots is intermediate (Table 2). However, the mean comparison analysis (Table 3) reveals that there is no significant difference between average yields according to irrigation methods (p-value = 0.11). Furthermore, the interaction between land management and irrigation shows a significant trend (p-value = 0.05), indicating that the influence of irrigation varies according to the type of land management. This implies that specific combinations of land management and irrigation methods contribute to higher yields. For example, the combination of Smart-valleys with low constant irrigation (IR2) tends to produce the best yields, suggesting that integrating this technology with appropriate water management is beneficial. This configuration could optimize water availability without causing stress, meeting the plant's needs throughout its cycle. Multiple linear regression analysis was performed to confirm these results (Table 4). From this analysis, SV layout has a positive effect on yield with a p-value of 0.03, indicating a significant trend at the 5 % threshold. This effect indicates that the SV tends to increase yield by 1.92 units compared to the reference land management (AC). The regression analysis also confirms that neither IR2 (p-value = 0.47) nor IR3 (p-value = 0.32) have a significant effect on yield compared to the reference irrigation IR1. Figure 2 shows the observed effects.

Table 2Average rice yield by land management and irrigation methods.

a Non-significance, b significance.

3.2 Effect of factors on water productivity

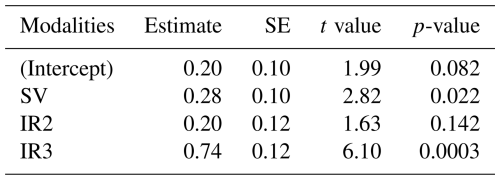

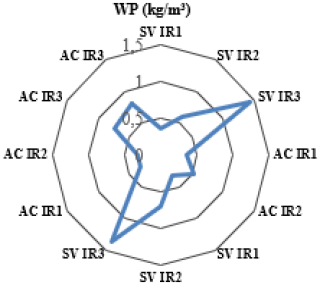

Table 5 shows the water productivity values for the two factors. From the analysis in Table 5, the average water productivity (WP) value was highest in the AWD (IR3) treatments, followed by the constant low-level irrigation (IR2) treatments. The lowest WP value was recorded in the variable water level irrigation treatments (IR1). We also observed that the WP value increased with Smart-valleys developments. According to the interactions, the highest WP (1.40 kg m−3) and lowest WP (0.34 kg m−3) were observed in the Smart-valleys treatments with intermittent irrigation (SV-IR3) and conventional development with variable irrigation (AC-IR1), respectively. Analysis of variance allows for an assessment of the effect of different management methods and irrigation practices on water productivity. The ANOVA results (Table 6) show significant differences in water productivity depending on the management methods, irrigation strategies, and their interaction (p-value < 0.001, p-value < 0.001, and p-value < 0.005). This suggests that these factors independently and jointly influence water use efficiency in the rice production system. Indeed, Smart-valleys plots have a significantly higher average WP (0.79 kg m−3) compared to conventional developments (0.51 kg m−3). This reflects better water management in smart valleys, probably due to improved water control and reduced losses. Irrigation strategies show a clear hierarchy with IR3 (intermittent irrigation) achieving the highest WP (1.08 kg m−3), followed by IR2 (low constant level, 0.54 kg m−3) and IR1 (variable level, 0.34 kg m−3). This suggests that intermittent irrigation optimizes water exchange and oxygen availability for roots. The interactions between land management and irrigation reveal that the SV-IR3 combination is the most efficient (1.40 kg m−3), confirming that smart valleys maximize the potential of intermittent irrigation. In contrast, the AC-IR1 and SV-IR1 combinations show the lowest performance, indicating that these methods are less suitable for optimal water resource management. Regression analysis (Table 7) confirms these trends, indicating that SV management has a positive effect, with an estimated coefficient of 0.28 (p-value = 0.022), indicating an increase in water productivity compared to conventional management. With regard to irrigation, the IR3 (intermittent irrigation) method has a significant effect on water productivity (coefficient = 0.74; p-value < 0.001), suggesting increased efficiency compared to other methods. These results are illustrated below (Fig. 3).

3.3 Discussion

The results of the study showed that the type of land management directly influences rice yield (p-value = 0.01), unlike irrigation methods (IR). For instance, Smart-valleys (SV) management approach has a positive effect on rice yield, with an increase of 1.92 units (p-value = 0.03). This finding suggests that SV approach, by maintaining a consistent and sustainable water depth in the fields, effectively contribute to improving rice production yields. Similar results have been obtained in several regions of West Africa where the approach has been widely adopted (Arouna et al., 2017; Arouna and Akpa, 2019; Bama et al., 2020). According to these studies, smart-valleys offer better agronomic and economic performance for farms in a context of climate change. With regard to irrigation methods, the results indicate that neither IR2 nor IR3 have a significant effect on yield compared to the reference irrigation method IR1. However, all the methods tested produced results higher than the average yield of 3.1 t ha−1 obtained in the area (MAEP Bénin, 2019). This suggests that, unlike continuous flooding, using an alternative irrigation system based on wetting and drying, as advocated by SRI, is beneficial for optimizing rice yields. Gbenou (2013), Mannan et al. (2012), Mohd Khairi et al. (2015), and Yakubu et al. (2019) all confirm this finding. In addition, water savings in rice fields, combined with good fertility management, maximize water productivity. Smart-valleys plots have a significantly higher average WP (0.79 kg m−3) than conventional systems (AC, 0.51 kg m−3). This reflects better water management in smart valleys, most likely due to improved water control and reduced losses from evapotranspiration and percolation. This trend is supported by data analysis, with p-values < 0.05 indicating a significant effect of land management approach, specifically Smart-valleys, on improving water productivity. Irrigation also has a significant effect, with p-values < 0.001, indicating that irrigation, particularly intermittent irrigation (IR3), influences water productivity variation. The irrigation strategies have a clear hierarchy, with IR3 (intermittent irrigation) achieving the highest WP (1.08 kg m−3), followed by IR2 (low constant level, 0.54 kg m−3) and IR1 (variable levels, 0.34 kg m−3). This indicates that intermittent irrigation improves water exchange and oxygen availability for roots. This is consistent with the work of Yakubu et al. (2019), who report that reducing water use increases rice water productivity. These findings are consistent with those of previous studies on water productivity (Nabipour et al., 2024; Ndiiri, 2013). For example, Ndiiri (2013) found that intermittent irrigation increases average water productivity by 140 % and 100 %, respectively, in experimental plots and farmer survey reports. According to these studies, better water management and an increase in organic matter for fertilization could further increase water productivity. The interaction between land management approach and irrigation practices strongly influences the response variable (p-value = 0.0027). The results revealed that the SV-IR3 combination performs best (1.40 kg m−3), confirming that Smart-valleys maximize the potential of intermittent irrigation (Nabipour et al., 2024). The LOV faces several socioeconomic constraints when implementing the Smart-valleys approach, including the availability of labor for soil preparation and annual floods that inundate plots. Indeed, the clayey texture of the soil makes soil preparation operations such as plowing, leveling, and building small dikes particularly labor-intensive. However, the scarcity of this resource makes these operations more difficult. According to Gbenou (2013), the primary causes of this situation are emigration to Nigeria and rural exodus. In addition to being difficult to access, labor has become expensive, thus compromising the profitability of the agricultural production systems implemented as part of this approach. Furthermore, annual floods destroy dikes and flood plots, increasing the costs of soil preparation in the implementation of the smart-valley approach in the LOV. Two types of rice production have been identified in the lower Ouémé Valley: rain-fed production on the plateaus and floodplain production, which spans from the short rainy season to the long dry season. Given the available resources, particularly labor, and the severity of the flooding, this study was conducted over a single season (rainfed production), which may limit the scope of the findings. Future research could focus on floodwater production to supplement our findings.

This research identified the appropriate land management approach and irrigation practices for efficient water management in rice production in the lower Ouémé valley. The various findings revealed that the Smart-valleys management approach significantly increases rice yields and water productivity in the study area. This also applies to intermittent irrigation (IR3), which encourages increased water productivity in rice farming. Furthermore, the combination of Smart-Valleys with low constant irrigation (IR2) and intermittent irrigation (IR3) improves yields and water productivity, implying that incorporating Smart-valleys technology followed by good water depth control is beneficial for rice production. The effective dissemination of these findings will help decision-makers and farmers improve and sustain rice production in the lower Ouémé valley. To emphasize the impact of climatic seasons on rice production, the study might, nevertheless, incorporate the flood recession production.

Statistical analyses were performed using R software (4.3.2). Custom scripts are available upon request from the respective author, as they contain site-specific data that cannot be made public.

Research underlying this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conceptualization, M.K.S. and L.O.S.; methodology, M.K.S. and D.H.A; data analysis, M.K.S.; manuscript draft preparation, M.K.S., D.H.A. and R.B.; supervision, R.B. and L.O.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

At least one of the (co-)authors is a guest member of the editorial board of Proceedings of the International Association of Hydrological Sciences for the special issue “Circular Economy and Technological Innovations for Resilient Water and Sanitation Systems in Africa”. The peer-review process was guided by an independent editor, and the authors also have no other competing interests to declare.

Publisher's note: Copernicus Publications remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims made in the text, published maps, institutional affiliations, or any other geographical representation in this paper. The authors bear the ultimate responsibility for providing appropriate place names. Views expressed in the text are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

This article is part of the special issue “Circular Economy and Technological Innovations for Resilient Water and Sanitation Systems in Africa”. It is a result of the 1st Edition of the C2EA Water and Sanitation Week on the Circular Economy and Technological Innovations, Cotonou, Benin, 3–6 December 2024.

The authors would like to express their deep gratitude to the Water Week organizing team for the rich and varied scientific exchanges. They also thank the reviewers for their scientific contributions to the quality of this work.

This research has been supported by the World Bank and the French Development Agency (AFD) as part of the thesis grants program of the African Center of Excellence for Water and Sanitation (C2EA) at the University of Abomey-Calavi in Benin.

This paper was edited by Moctar Dembélé and reviewed by Koffi Claude Alain Kouadio and Kouame Donald Kouman.

Agossou, G., Gbehounou, G., Zahm, F., and Agbossou, E. K.: Adaptation of the “Indicateurs de Durabilité des Exploitations Agricoles (IDEA)” method for assessing sustainability of farms in the lower valley of Ouémé River in the Republic of Benin, Outlook on Agriculture, 46, 185–194, 2017.

Ahouandogbo, C.: Analyse de la contribution de la gestion des aménagements hydro-agricoles pour la sécurité alimentaire dans un contexte de changement climatique dans la basse vallée de l'Ouémé, Thèse de doctorat, Université d'Abomey-Calavi, 212 pp., 2022.

Arouna, A. and Akpa, A. K. A.: Water Management Technology for Adaptation to Climate Change in Rice Production: Evidence of Smart-Valley Approach in West Africa, in: Sustainable Solutions for Food Security, edited by: Sarkar, A., Sensarma, S. R. and vanLoon, G. W., Springer International Publishing, Cham, 211–227, https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-77878-5_11, 2019.

Arouna, A., Akpa, A., and Adegbola, P. Y.: Impact de la technologie smart-valley pour l'aménagement des bas-fonds sur le revenu et le rendement des petits producteurs de riz au Bénin, Centre Béninois de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique, 21 pp., 1840-703X, 2017.

Bama, N. A. D., Dossou-Yovo, E., Gbané, M., Gnépi, E. V., Soulama, I., Ibrahima, O., and Adama, O.: Impact of Smart Valley on Soil Moisture Content and Rice Yield in Some Lowlands in Burkina Faso, Agricultural Sciences, 11, 860–868, https://doi.org/10.4236/as.2020.119055, 2020.

Bouman, B. A. M., Peng, S., Castaneda, A. R., and Visperas, R. M.: Yield and water use of irrigated tropical aerobic rice systems, Agricultural Water Management, 74, 87–105, 2005.

Dossou-Yovo, E. R., Devkota, K. P., Akpoti, K., Danvi, A., Duku, C., and Zwart, S. J.: Thirty years of water management research for rice in sub-Saharan Africa: Achievement and perspectives, Field Crops Research, 283, 108548, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2022.108548, 2022.

Fashola, O. O., Olaniyan, G., Aliyu, J., and Wakatsuki, T.: Comparative evaluation of farmers' paddy field system and the SAWAH system for better and sustainable rice farming in inland valley swamps of Nigeria, in: 5th African Crop Science Conference Proceedings, 615–619, 2002.

Gbenou, P.: Evaluation participative du Système de Riziculture Intensive dans la basse vallée de l’Ouémé au Bénin, Thèse de doctorat unique, Université d'Abomey-Calavi, 214 pp., https://sri.ciifad.cornell.edu/countries/benin/research/BeninPhdThesisGbenou13.pdf (last access: 12 December 2025), 2013.

Hounkanrin, J. B.: Mise en valeur agricole de la vallée de l’Ouémé dans la Commune de Bonou: diagnostic et trajectoire, Thèse de doctorat unique, Université d'Abomey-Calavi, 275 pp., https://theses.hal.science/tel-03786960/document (last access: 12 December 2025), 2015.

Kambou, D., Xanthoulis, D., Ouattara, K., and Degré, A.: Concepts d'efficience et de productivité de l'eau (synthèse bibliographique), Biotechnol. Agron. Soc. Environ., 18, 108–120, https://orbi.uliege.be/handle/2268/162650 (last access: 12 December 2025), 2014.

Kouhoundji, N.: Problématique de la maîtrise de l’eau agricole dans la basse vallée de l’Ouémé à Sô-ava, Mémoire de Maîtrise en Géographie, Université d'Abomey, 102 pp., https://www.memoireonline.com/04/12/5650/Problematique-de-la-matrise-de-leau-agricole-dans-la-basse-vallee-de-lOueme–S-Ava.html (last access: 12 December 2025), 2010.

MAEP Bénin: Stratégie Nationale de Développement la Riziculture-deuxième génération (SNDR 2) (2019–2025), https://riceforafrica.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/NRDS2_Benin_fr.pdf (last access: 12 December 2025), 2019.

Mannan, M. A., Bhuiya, M. S. U., Akhand, M. I. M., and Saman, M. M.: Growth and yield of basmati and traditional aromatic rice as influenced by water stress and nitrogen level, Journal of Science Foundation, 10, 52–62, 2012.

Masiyandima, M., Mufwaya, C., and Kizito, F.: Assessing water resources potential for increasing rice production in the Oueme River basin, Benin, 3rd Africa Rice Congress, Yaounde, Cameroun, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/286884014_Assessing_water_resources_potential_for_increasing_rice_production_in_the_Oueme_River_basin_Benin (last access: 12 December 2025), 2013.

Mohd Khairi, M. K., Mohd Nozulaidi, M. N., Ainun Afifah, A. A., and Md Sarwar Jahan, M. S. J.: Effect of various water regimes on rice production in lowland irrigation, Australian Journal of Crop Science, 9, 1835–2707, 2015.

Montgomery, D. C., Peck, E. A., and Vining, G. G.: Introduction to linear regression analysis, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-1-119-57872-7, 2021.

Nabipour, R., Yazdani, M. R., Mirzaei, F., Ebrahimian, H., and Alipour Mobaraki, F.: Water productivity and yield characteristics of transplanted rice in puddled soil under drip tape irrigation, Agricultural Water Management, 295, 108753, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agwat.2024.108753, 2024.

Ndiiri, J. A.: Water productivity under the system of rice intensification from experimental plots and farmer surveys in Mwea, Kenya, Taiwanese Water Conservancy, 61, 63–75, 2013.

Seidou, S., Ouassa, P., Atchade, G., and Vissin, E. W.: Caractérisation des risques hydroclimatiques dans la Basse Vallée de l'Oueme Au Benin (Afrique de l'Ouest) [Characterization of hydroclimatic risks in the Lower Valley of the Oueme in Benin (West Africa)], International Journal of Progressive Sciences and Technologies, 25, 334–348, 2021.

Thakur, A. K., Rath, S., Patil, D. U., and Kumar, A.: Effects on rice plant morphology and physiology of water and associated management practices of the system of rice intensification and their implications for crop performance, Paddy Water Environ, 9, 13–24, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10333-010-0236-0, 2011.

Yakubu, A., Ofori, J., Amoatey, C., and Kadyampakeni, D. M.: Agronomic, water productivity and economic analysis of irrigated rice under different nitrogen and water management methods, Agricultural Sciences, 10, 92–109, 2019.